On Performative Cinema - On the films of Roland Sabatier

Is it possible to make films with words? To borrow the terminology put forward by Austin, can cinema in certain instances be performative?1 Can a linguistic utterance take the place of the film itself? I would like to develop this hypothesis in relation to the films of Roland Sabatier, which combine the dematerialisation of the artwork with a certain conceptualism.

Roland Sabatier belongs to the Lettrist movement. His early works date from 1963. Together with Maurice Lemaître he was one of the main artists in the group to develop a cinematographic project on a consistent basis. It is difficult to describe his work without evoking the context of the Lettrist avant-garde, which emerged at the end of World War II under the leadership of Isidore Isou, and looked beyond the aesthetic field towards a general revolution of knowledge. Note that Lettrist cinema was analysed and commented upon mainly by Lettrist artists themselves, in keeping with the movement’s characteristic tendency to develop its own historiography, couched in a distinctive critical language, using neologisms, and marked by the publication of manifestos and articles in Lettrist books and journals.

Following his film Traité de bave et d’éternité (Treatise on Venom and Eternity) in 1951, Isou published his Esthétique du cinéma. Here, he applied a number of original concepts, including the decisive notions of the amplic (amplique) and chiselling (ciselant).2 According to Isou, the arts go through two alternating phases: the amplic, characterised by the plenitude of stylistic devices and artistic resources, and the chiselling phase, which involves the destruction and negation of the medium, via the atomic dissociation of its elements. Cinema, he says, has entered its chiselling phase, hence the Lettrist strategies of destroying the support, scraping surfaces, discrepancy, that is to say, the dissociation of the sound track and the image track. This feeling of closure expressed by Isou is striking as he tries to develop the powers of the medium after its disappearance. “I announce the destruction of cinema, the first apocalyptic sign of disjunction, of rupture, of that swollen and potbellied organism that is called film,” he states in his film. But Lettrist cinema should not be limited just to the chiselling and discrepant tendency. In 1952 Isou published his book Amos ou Introduction à la métagraphologie, described as a “hypergraphic film” constituted by photographs enriched with signs painted with gouache. Hypergraphia consists of a synthesis of visual and linguistic signs that may find filmic expression in book form by mixing writing, photography and drawings. Film is detached from its technical apparatus and takes the form of a book or a photographic sequence. In his book Le film est déjà commencé ?, published in 1952, Maurice Lemaître describes the actions to be performed by actors during the session, establishing a structural link between book, performance and film.3 Also worth mentioning are two decisive concepts that are productively expressed in the work of Roland Sabatier: imaginary or infinitesimal art, exhibited as of 1956 by Isou, who rarefies sense data in favour of intangible or mental expression, close to conceptual art, and super-temporal art, in which the artist proposes a simple creative framework that viewers, who have become users, can take over in order to develop or even contradict the work that is proposed, without temporal limits.4 Let us note the way in which Lettrist films try to go beyond the limits of their medium, to make what Pavle Levi’s essay argues is Cinema by Other Means.5

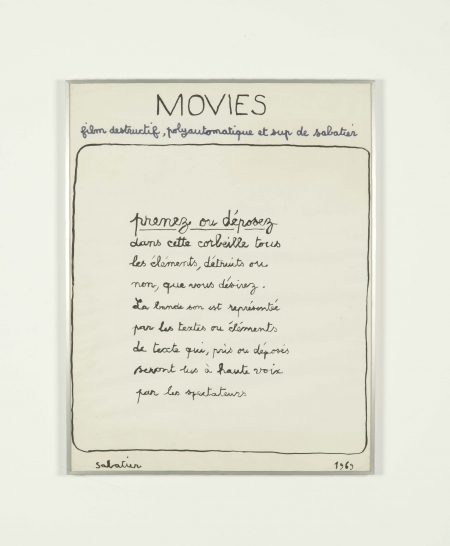

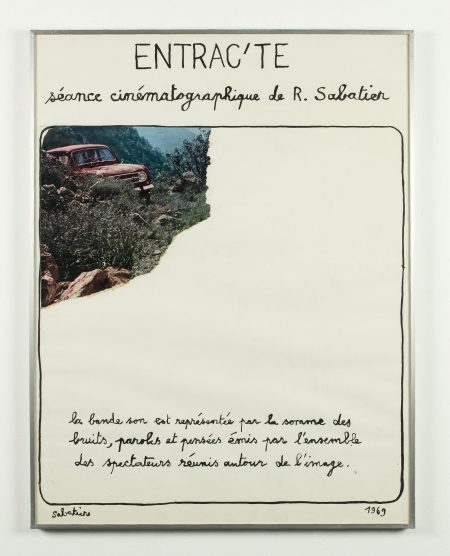

Roland Sabatier explored these different tendencies on the critical side of “aesthetic polythanasia,” which defines the varied and complex forms of destruction and negation of the artwork.6 His cinematographic work does effectively strive to suppress or deny the very characteristics of the medium. We can get an idea of his cinematic project from Œuvres de cinéma (1963-1983), a 128-page A4 book, probably photocopied or roneotyped, made up uniquely of data sheets.7 Each of the artistic propositions adopts a standard form, familiar from traditional cinema: original title, date of filming, production, presented in various categories – film format (16 mm, super-8, film/action, video), running time, length (metres), number of reels, silent/sound, black-and-white/colour, performers, public certification and publications. A short description (a script) presents the project. Two technical indications have no place in traditional cinema: the “film/action,” presented as a possible format, and the certification, which reflects the Lettrist insistence on editorial, administrative inscription, with a view to establishing the work’s historical primacy. The first edition of this book, Œuvres de cinéma (1964-1978), was published in 1978 (the second came out in 1984). The circumstances of its publication are enlightening. Like Maurice Lemaître and Isidore Isou, who obtained their doctorates “for practical work” in 1974 and 1976, respectively, the author was preparing a thesis on “The internal and external destruction of art” at the Centre Universitaire de Vincennes under the supervision of André Veinstein.8 In order to strengthen his dossier, he prepared a first edition of this book in what, he said, was a fairly rapid way. Œuvres de cinéma was published by Éditions Psi, founded by Sabatier himself in 1963, in order to propose an “independent and supple editorial framework capable of certifying and propagating without any external constraints his own creations and those of other artists in the Lettrist movement.”9 This feature is typical of the editorial logic of the Lettrists, who were engaged in the documentary production of archives and viewed art history as an aesthetic form.10 For this book, Sabatier wanted to use a “cinematographic norm” by choosing a data sheet that enabled him to “separate cinema from visual art.” The point was to emphasise the profoundly cinematographic nature of his films, in spite of appearances to the contrary. Most of the films are without film stock. The sound is made in the theatre and the running time is indeterminate. Writing about Lettrist cinema in general, Sabatier notes that “In fact, it was in their overflowing of what was that these films, in most cases, were unlike films as commonly understood, for the cinema that they reveal is a cinema on the limits and on the outside of cinema. It does that in order to be cinema that is other, constantly inviting the spectator more to intellectual adventure than to contemplation.”11

While the idea of radical work that pushes at the limits of the medium in sessions of expanded cinema and performances is something we can understand fairly well, the publication of Œuvres de cinéma continues to surprise. Most of the sheets describe films that were never made, performances that did not take place, projects that were never realised, described in the form of simple hypotheses, granting the wish expressed by Édouard Levé: “A book describes works conceived by the author, but that he did not make.”12 The film’s technical data (the script) has become the film. Are we in the presence of a category of paper film? By its artisanal character, its recourse to self-publication, and above all the description of films whose existence rests mainly on their linguistic articulation, the book seems to belong in the sphere of the performative. What is the status of these technical data? Sabatier tends to speak in terms of projects, even if the status of these documents may suggest other terms: score, instruction or injunction, for example. “What people may call them is indifferent to me. I never raised the problem. One could also say score, as a generic term for a project. A synonym for project. How should one say that? A list. One brings together all the elements. A kind of guide.”13 It would seem, however, that the virtual dimension of the films was not totally premeditated or intended. “Wishing to position myself truly within cinema, I conceived these films which are intellectual conceptions. They open onto a few practical considerations, but no one has never proposed that I show them. If I had had to show them, I would have been more interested in the way of presenting them while preserving their anti-cinema characteristics.”14 Failing that, then, he published them. But was the absence of production fortuitous? Could we not interpret the act of publication as a performative?

It is striking fact that Sabatier’s cinema often assumes a script (an utterance, a text, a suite with dialogues) as part of its activation. If the film is sometimes reduced to the simple statement of a project, published in the book in the form of a description, some films also invoke a second script that must be activated at a cinema session. Can the technical sheet be interpreted as a performative document? “A performative document is thus a document that is not exhausted in the act of documenting; it transforms the way of being – the ontological status – of what it documents. It turns an ordinary or extraordinary action into an artistic action.”15 This seems to be what the data sheets published by the artists do. We can distinguish three modalities: the data sheet describes a performance based on a second script, following a simple procedure (Hommage à Buñuel, 1970); the technical data describe a performance that is based on a performative script in accordance with modes of presentation that are complex, labile, diversified, and capable of existing in multiple versions (Regarde ma parole qui parle le (du) cinéma, 1982); the data sheet is a simple performative utterance which is accompanied by an editorial strategy (Le film n’est plus qu’un souvenir, 1975).

1. “The author tells the audience what the film will be by giving details about the contents of the sound and image. After a moment of description, he ends by saying: ‘I will therefore not make this film, but imagine what it could have been on the basis of the few indications that I have just given you.’”16 Hommage à Buñuel, “a polythanased hypergraphic film,” was presented by the author at the Cinémathèque Française on 23 April 1970. This simple description implies a second script, read by the author to the public, describing the imaginary work that should have been projected. This was a “hypergraphic film” that combined different écritures and visual signs forming a rebus. “Again as an example, another image shows a portrait of the maker of this film looking spectators in the eye (je)… / Against a black ground, the syllables ‘PEN’ and ‘SE’ (pense [think])… immediately completed by an/Image in line with the tail of a cow (que [that/tail])… / I repeat that this is only an example designed to enable you to grasp the way the film is conceived.”17 The text read by the artist ends with these words: “By now, with regards to the film… you know as much as its maker, and since the latter is not inclined to concretely translate it onto the film, he suggests that you enter with him into the supplementary originality of non-realisation and imagine, as he himself does at certain moments in his life, what this film could have been based on the indications that he has just given in front of you. This film will therefore remain as it is, hanging from the lips of Roland Sabatier, its promoter, forever!” The technical data list describes a performance that is itself performative, which activates the film through its linguistic articulation in accordance with the principles of imaginary or infinitesimal art.

2. Let us consider a more complex work, Regarde ma parole qui parle le (du) cinéma, dating from 1982. The script of the film comprises a sound section constituted by the recital of technical terms (“close-up, middle shot, close-medium shot…”), and a visual section which relates a narrative using indirect libre discourse. “A man, no doubt sitting at a café terrace, who later turns out to be a filmmaker, perhaps the author himself, speaks, as if giving his personal thoughts, about the general and specific problems of innovative cinema.”18 Classic films from the history of cinema are evoked during a reflection on the power of the medium. The film plays on the reversals of saying and showing. “Look at my speech which speaks of cinema, and you shall see my film. While the images that make up cinema will be made available for hearing, the speech that talks about cinema will be shown as a film.”19 The sound track, with regard to the visual technical indications, must be recorded and played in the theatre while the text is read by the spectator, reproduced on film or on slides, or printed in a booklet and given out to the audience. Originally, I wanted parts of the text to appear on the screen and for a voice to be speaking technical terms such as close-up, etc. I had to give up on that formula,” the artist admits.20 Consequently, the work has been through many different versions: drawings in graphite, text printed on cards, photographs on slides or filmed. While the author was preparing a version for the International Avant-Garde festival in November 1983, the laboratory lost the roll of photographs. A replacement version shows fragments of filmed text but technical problems make the text illegible. A last version on DVD in 1996 presents printed inserts and a few photographs excerpted from films cited in the film, whereas the text is read on the sound track by the author. This lability of the versions underscores the performative nature of the script, as if the difficulty of presenting the film, beyond unfortunate circumstances and technical accidents, was constitutive of the work. “He had the impression that it was not enough for him to say ‘cinema’ for it to be a film, or nearly a film. It is somewhere, around this word CINÉMA, and above all in this ‘almost’ that the originality of the film no doubt lies.”21 The work evokes the register of the almost by developing the ‘not,’ the quasi, thereby recalling the figure of Bartleby. How far can cinema remain itself when destroying its own constituents? Can its definition proceed via negation or subtraction? “The film, certainly, can reside in the words that designate it.”22

3. A last example: Le film n’est plus qu’un souvenir, dating from 1975, a “polythanased film” of variable duration, without film stock, with various documents and accessories. I quote from the data sheet: “The author steps towards the public and, looking embarrassed, announces that he has made a chiselling film, but that this film has just been destroyed and therefore cannot be screened. In the end he offers to replace this work with the presentation of a certain number of documents bearing witness to its past existence. The new film, which is never named as such, occurs in the allusions to the films it is replacing and is manifested by the confused and awkward exhibition of various elements: tools, studio photos, bits of leftover film stock, etc., not to forget false press cuttings concerning echoes and reviews which, according to him, are related to the absent film or that served to make it.”23 The performance described has never been activated. It exists only in the enunciation by the book Œuvres de cinéma. And yet there are documents relating to this film, notably a photograph that is often produced in catalogues, captioned “The film is no more than a memory,” and representing movie accessories (film reel, projector, director’s chair, camera, tripod).24 One might think that it was a photograph of a public exhibition when in fact it is a studio photo taken by the artist in Aubervilliers. For Sabatier, the difference is non-existent. The only thing that matters is the artistic proposition and its date of certification. But is this a performative photograph which makes a work exist by a series of false indices playing the role of triggers of fiction? In this respect, the technical data sheet is a paradoxical performative utterance because the film is forever withheld from any kind of visibility. One might wonder about the closeness of Sabatier’s cinema to conceptual art. We could certainly mention the use of administrative procedures (the data sheet), the linguistic definition replacing experience (the performative utterance instead of the projection of the film), the critique of reification (the film destroyed), the juridical contract linking the work to its reception (Lettrist certification), and the taking into account of reception by the spectator (the imaginary or infinitesimal dimension). No doubt the performative dimension casts doubt on the nature of the artistic propositions, which are halfway between linguistic utterance and its possible activation.

Although the artist does not lay claim to this quality, the performative does allow us to analyse the internal logic of his cinematic propositions. His cinema usually presupposes the activation of a script. However, it is possible to wonder about the relation to failure. We may recall that this question is central to Austin’s ideas: three of the lectures in his book are about this subject. A performative can fail if certain conditions are not met: the right context, appropriate people, the sense of sincerity. “There must exist an accepted conventional procedure having a certain conventional effect, that procedure to include the uttering of certain words by certain persons in certain circumstances.”25 If this is not the case, the performative statement becomes unfortunate, to degrees analysed in detail by Austin. If we consider the earlier works, we will observe that that they too must fulfil a number of conditions in order to be operative. A context is always presupposed, whether it is an invitation to an event or a festival. With regard to Hommage à Buñuel, Sabatier states: “It was a session that we dedicated to Langlois, director of the Cinémathèque Française. If you are looking at a big screen and you don’t show a film and you show something other than a film, it is necessarily an anti-film. That was kind of the idea I started with. So, it’s not so simple if you present it in a gallery. That is why I stuck with cinema.”26 The cinema theatre seems to be a necessary condition for the success of the performative. “I based myself on this text,” he says with regard to a second script read during the performance. “I had to do it fairly quickly because people were joking around in the seats. I did a quick summary, because I realised it couldn’t last too long.”27 The conditions of performativity, clearly, were not always fulfilled. Seriousness, Austin insists, is another condition of success. The performative statement, if it is to be effective, requires in this situation a context of invitation, a cinema theatre, but also spectators conscious of what is at stake in the experiment. It would seem to be rare for all these conditions to be met. Likewise, quite apart from their incidental nature, the series of technical accidents (roll of film lost by a laboratory, text illegible due to clumsy filming) indicates the risks of failure attendant on the performative. Hence the question: should the work be realized? Is not the data sheet itself, strictly speaking, the performative film? Sabatier’s cinema is located at the interface of two tendencies. It comes across as a pure, almost conceptual linguistic utterance, but leaves open the possibility of its activation. The scarcity of realized performances, of course, is due to a number of factors. But we should emphasise the modest economy of the work. Technical accidents are the sign of an extreme poverty of means. The non-realization of the works also has to do with institutional and, I would say, sociological difficulties. The conditions of the performative imply, according to the analysis by Pierre Bourdieu, “effects of symbolic domination.”28 This situation can be used to analyse the position of Lettrism in the history of art, but I believe that the possibility of failure creates an opening to the project, at once experimental and participatory, in proportion to its promise, close to the vocation of the “coming film.” The script remains an open, labile statement, on the threshold of the film and the real, proposing “white surfaces, brief injunctions, dissimulated spaces or, ultimately, anything or nothing,” conducive, in the artist’s words, to “the power of a beyond-reality that is an impossible reality, that will never exist, that can never even be imagined – and is, in this sense, unimaginable, rather than imaginary.”29

Erik Bullot

1 John Langshaw Austin, How To Do Things with Words (1962), Harvard University Press, 1975.

2 Isidore Isou, Esthétique du cinéma [1952], Ion, Paris, repr. J.-P. Rocher Éditeur, 1999. Cf. Frédérique Devaux, Le Cinéma lettriste, Paris, Paris Expérimental, 1992.

3 Maurice Lemaître, Le film est déjà commencé ?, Paris, Éditions André Bonne, 1952.

4 Cf. Isidore Isou, Introduction à l’esthétique imaginaire et autres écrits: Paris, Cahiers de l’Externité, 1999.

5 Pavle Levi, Cinema by Other Means, Oxford University Press, 2012.

6 Isidore Isou, “Manifeste de la polythanasie esthétique” in La Loi des purs, Aux Escaliers de Lausanne, 1963

7 Roland Sabatier, Œuvres de cinéma (1963-1983), Paris : Publications Psi, 1984. Preface by Frédérique Devaux, ‘Roland Sabatier: De la reproduction à la représentation ou le cinéma en limite du cinéma.’

8 After ten years of enrolment as a doctoral student, Sabatier decided not to defend his thesis, although he had obtained all the necessary university credits.

9 Online presentation by Éditions Psi: www.lecointredrouet.com/lettrisme/psi.html

10 Cf. Fabrice Flahutez, Le lettrisme historique était une avant-garde, Dijon: Presses du Réel, 2011.

11 Roland Sabatier, “L’anti-cinéma lettriste : le cinéma sans le cinema,” in L’anti-cinéma lettriste 1952-2009, exh. cat., Sordevolo, Zero Gravità, 2009, p. 54.

12 Édouard Levé, Œuvres, Paris: P.O.L, 2002, p. 7.

13 Conversation with the author, Paris, 16 April 2013.

14 Ibid.

15 Stephen Wright, “Visibilités spécifiques,” Cahiers du post-diplôme, no. 3, Angoulême-Poitiers, École Européenne Supérieure de l’Image, 2013, p. 30.

16 Œuvres de cinéma (1963-1983), op. cit., p. 29.

17 Document provided by the artist.

18 Roland Sabatier, Trois films sur le thème du cinéma. “Regarde ma parole qui parle le (du) cinéma. 1982,” “Quelque part dans le cinéma. 1982,” “Une (certaine) image du cinéma. 1983,” Paris, PSI, 1983, p. 13.

19 Ibid., p. 25.

20 Conversation with the author, Paris, 16 April 2013.

21 Trois films sur le thème du cinéma, op. cit., p. 27.

22 Trois films sur le thème du cinéma, op. cit., p.

23 Œuvres de cinéma (1963-1983), op. cit., p. 60.

24 For example, on the cover of the journal Zehar, no. 56, May 2006 or in L’Anti-cinéma lettriste, op. cit., p. 96-97. Other elements from this set of objects were exhibited in a display case when he had a solo show at the Galerie Artcade, Nice, from 17 September to 20 October 1992.

24 J. L. Austin, How To Do Things with Words, op. cit. p. 14.

25 J. L. Austin, How To Do Things with Words, op. cit. p. 14.

26 Conversation with the author, Paris, 16 April 2013.

27 Ibid.

28 Pierre Bourdieu, Ce que parler veut dire, Paris: Fayard, 1982.

29 “L’anti-cinéma lettriste : le cinéma sans le cinema,” op. cit., p. 58.

This exhibition is part of

Inférences et Modalités

En dehors d’un certain nombre de films encore inscrits sur la pellicule, comme Le Songe d’une nudité (1968), Évoluons (encore un peu) dans le cinéma et la création (1972), Pour-Venise-Quoi ? (1994), ou encore Propriétés d’une approche (2008), la plupart de mes réalisations renoncent aux supports filmiques traditionnels pour se présenter comme des films parfois sonores, souvent sans image et, plus fréquemment encore, comme des réalisations destinées, non plus à être projetées dans la pénombre, mais à être exposées en pleine lumière. De ce point de vue, toutes les œuvres filmiques choisies par Éric Fabre pour figurer dans Anti-cinéma (lettriste) & Cinémas lointains (1964-1985) sont représentatives de cette démarche purificatrice explorée jusque dans ses conséquences les plus extrêmes vers les limites au-delà desquelles un film ne ressemble plus à un film.

Rejoignant la modernité atteinte avant lui par la peinture, la poésie, la musique ou le roman, ce mode cinématographique finit par ne plus être qu’une réflexion sur le cinéma avant de s’achever dans la moquerie grossière de ce que ce dernier avait été autrefois. Comme dans un musée, « il se fait du simple déballage des éléments qui, autrefois, servaient à faire le cinéma». Ainsi, dans le but de se jouer du cinéma, l’auteur « redevient l’enfant qui joue au cinéma et devient l’ancien cinéaste qui regarde nostalgiquement son passé et celui de son art ».

Comme expressions de l’achèvement et de l’anéantissement du cinéma ciselant, hypergraphique, infinitésimal et supertemporel, ces œuvres s’imposent comme des entités autonomes. Comme telles, elles existent déjà dès l’instant où elles sont (dé-) écrites et publiées. Leur matérialisation éventuelle, secondaire — possible ou non —, peut dès lors être entreprise de différentes manières selon le lieu et le contexte où elles seront portées à la connaissance du public : salle de cinéma, d’exposition, distribution dans la rue ou autres. Ces mises en œuvre potentielles n’apportant que des enrichissements secondaires, propres aux mécaniques ou cadres ponctuellement sélectionnés pour des circonstances données, sans altérer ni modifier la substance formelle intrinsèque des faits esthétiques.

Cette disposition justifiant la réalisation pour chacun de ces films d’un certain nombre de variantes ou de modifications qui ne sont que des adaptations possibles de leurs fondements premiers, seuls essentiels.

Roland Sabatier