For the occasion of Ink Brussels 2019, Garage Cosmos presents artworks by Salvador Dalí, Isidoare Isou, David Mach, Sarkis and Gil Wolman, that incorporate ink as a three-dimensional medium. The ink is contained in bottles, jars, bowls or glasses. The artists do not apply techniques of ink painting on paper, they do not manipulate the ink but leave it as is, considering the ink itself as the artwork. They thus disrupt established canons of beauty that emphasise the expression of individuality, deconstructing traditional frameworks to expand the possibilities of ink.

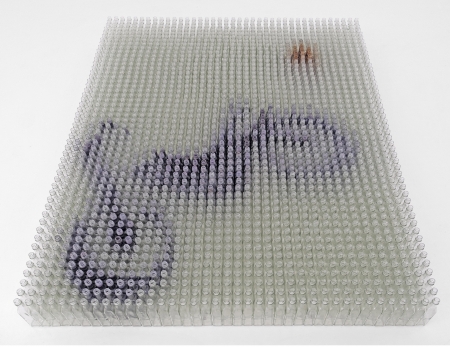

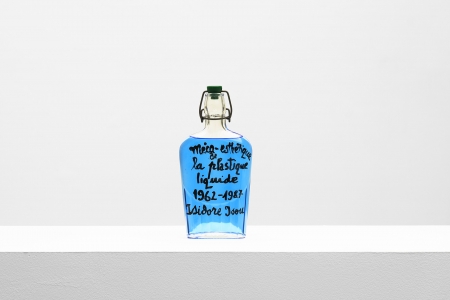

Salvador Dalí’s surrealist object Monument à Kant (1936) stems from his fascination as a student for the philosophical writings of Immanuel Kant. It includes a miniature replica of Kant’s tombstone which contains a passage from his Critique of Pure Reason in the original German: ‘Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry skies above me and the moral law within me.’ Dalí recontextualises the found object by assembling it with a Chartreuse bottle, glasses and dip pens. Isidore Isou’s Méca-esthétique de la plastique liquide (1962-1987) is a closed glass bottle on which he wrote in black the title of the work, its date and his signature. The bottle can be filled with any liquid. The concept of ‘meca-aesthetics’, which he formulated in 1952, regroups all the supports, materials and tools, acquired or possible, used for artistic creation, with the aim of creating new means and mechanics of realisation. Following the definition of meca-aesthetics, Gil J. Wolman presented the installation Ensemble de peintures liquides at the Salon Comparaisons in 1962. With Fallen Angel (1982) David Mach arranged glass bottles filled with blue and red ink into the image of a motorbike, which appears and disappears depending on the angle from which it is viewed. In a series of short films started in 1996 Sarkis has created living paintings by dissolving watercolours in bowls of water and allowing for unexpected mutations and expansions of colours to occur.

Ink can indeed be used in many ways without the intermediary of the brush and paper. As advanced by Chinese artist and curator Zhang Yu in the title of an exhibition he curated in 2008 ‘Ink is not equal to ink painting’. Although contemporary art practices introduced from the West in the 20th century have to some degree challenged the primacy of ink art in China, it has been used by Chinese contemporary artists who rank amongst the most radical such as Qiu Zhijie and Zhang Huan as an element in new media works, video art, performance and installations. They address the frameworks of traditional Chinese ink painting and calligraphy while being informed by western art practices. Therefore, if we consider such works as contemporary ink art, might it be possible to extend the boundaries even further so as to include works by western artists who do not make direct references to traditional forms of ink painting and calligraphy, but rather explore its conceptual potential? A cultural dialogue can lead to an enriched understanding of ink and to fresh ideological forms of ink art. Indeed, a globalized context requires transcending cultural hegemony and the rigid confrontation between China and the West in order to allow for a total union of cultures. Just like in Chinese the expression ‘to read a painting’ refers to studying and appreciating a painting, where there is no one-point perspective but rather a moving focus as the eyes wonder through the landscape, ink art may be read from various standpoints.

Furthermore, while the artists featured in the exhibition all work with found objects to create sculptures and installations, they are also theorists, poets and painters. Thus, a parallel may be drawn with the Chinese literati who were scholars, painters, calligraphers and poets. First formulated in the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), the Chinese literati ideal evolved from the all-important domain of calligraphy which made use of the Four Treasures: the brush, paper, ink and inkstone. The Four Treasures were considered artforms in their own right and were often the themes of paintings, calligraphies and poems, such as ‘Inscribed on My Grass-script Calligraphy Written While Drunk’ by Lu Yu (1125-1210):

I seize upon wine as banners and drums, and make of my pen a long lance;

Heaven-born strength comes to men like the Silver River rushing down.

On the inkstone hollow from Duan Brook, I grind my ink thick;

Under the flitting candlelight, my pen crisscrosses as if flying.

In a moment I roll up the scroll and take again my wine cup,

As though all across ten thousand li had been cleared of dust and smoke!

Reviving the literati ideal by showcasing ink as a ‘treasure’ may reinstate a much needed cultural basis to contemporary art, at the same time as it widens horizons and stimulates the imagination.

Curator: Rosalie Fabre

Opening hours: Friday to Sunday between 1– 6pm

Preview: Friday, 10 May between 6 – 8pm

Exhibition: 11 – 26 May 2019

Ink Sculptures

Salvador Dalí, Isidore Isou, David Mach, Sarkis, Gil Wolman

11 May – 26 May 2019